I.

The year I finally understood who I was, I didn’t make anything. I just kept things.

I kept a playlist called “4am eternal” that I never showed anyone. I kept screenshots of tweets that felt like they were written about me specifically. I kept a list of quotes organized by vibe. I kept a folder on my desktop called “for later” that I knew I would never open again. I kept an Obsidian vault with 8,472 notes but never quite got around to connecting it to Claude Code. I kept recipes I’d never cook and essays I’d never finish reading and voice memos that started mid-sentence and ended nowhere.

I also kept—and I’m telling you this because if I don’t, the rest of this essay is a lie—a single voicemail from my father, nine seconds long, that just says in Tagalog, “Call me back when you get this, it’s nothing important.” I have listened to it maybe two hundred times. He is still alive. It is still nothing important. I keep it anyway, in a folder I pretend I don’t remember exists.

At the end of the year, Spotify told me I was a “Collector.” It said I was part of a club. It showed me what I had gathered and asked me to share it with everyone I knew.

I did. We all did.

Two hundred million people opened their Wrapped within the first day. Not what they’d made. What they’d kept.

II.

In 1986, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote an essay that no one read at the time and everyone has been paraphrasing ever since. It was called “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” and the argument was simple enough to miss entirely.

The dominant story we tell about being human goes like this: Man picked up a weapon. He killed a mammoth. He came home a hero. From that first triumph flows all of civilization—war, progress, conquest, the lone genius, the disruption, the arc.

But Le Guin pointed out that anthropologically, we didn’t survive by hunting. We survived by gathering. And for gathering, you don’t need a spear. You need a bag. Something to hold what you find. Something to carry it home.

The container, not the weapon, was the first technology.

Le Guin’s point wasn’t that the hero story is false—people did hunt, mammoths did fall. Her point was that we chose it. We had two technologies, two forms of survival, two ways to make meaning. We built a civilization on the one that made for better stories.

III.

The obvious version of this essay—the one that would kill on Substack—goes: We live in a playlist age, identity through curation, the feed as carrier bag, we’ve all become gatherers, how lovely, how Le Guin.

That version is boring because it’s self-congratulatory. We haven’t escaped the hero narrative just by switching containers.

What’s actually happening is stranger and less resolved.

IV.

The album was a hero’s journey. Dark Side of the Moon takes you somewhere and brings you back transformed. Blonde is a descent and an emergence. These are arcs. They have climaxes. They conquer your attention and remake you in their image.

The playlist doesn’t do this. The playlist holds songs in relation. It doesn’t go anywhere. It doesn’t climax. It has no author-genius imposing vision. It’s just things gathered together by someone who found them meaningful.

And yet: the playlist has become how we know ourselves.

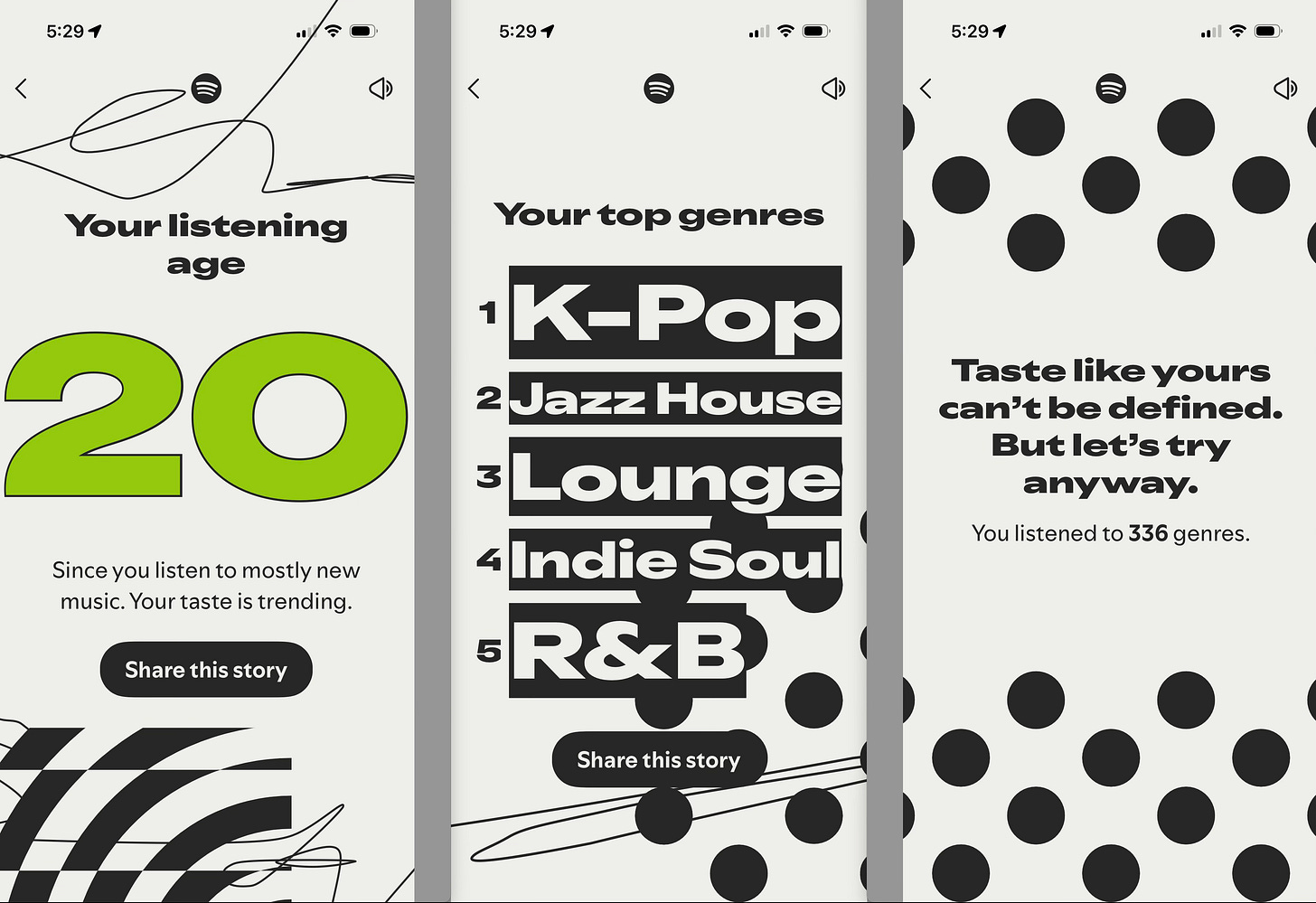

Spotify Wrapped isn’t just a marketing campaign. It’s an annual ritual of selfhood. Two hundred million people sharing what they gathered. What they kept. What they returned to in the dark. The feature “turns listening habits into a narrative,” according to the behavioral scientists who study it—but that’s not quite right. It turns listening habits into a container. Here’s everything I held this year. This is what fit in my bag.

The album tells you who the artist is. The playlist tells you who you are.

But here’s what I can’t stop thinking about: What happens to selfhood when identity is no longer something you build but something you accumulate?

A hero earns their identity. They go through trials. They transform. The self at the end of the journey is different from the self at the beginning—that’s the whole point. But a carrier bag self doesn’t transform. It just gets fuller. The songs I saved in 2020 are still there under the songs I saved in 2025. Nothing is overcome. Nothing is left behind. The bag just gets heavier.

I don’t know what kind of self that produces. I don’t know if it’s a self at all, or just a pile. The self that “likes” Fred again.. and also “likes” Kpop and also “likes” a 67-minute hard techno Hertz mix is not a self with a center.

Maybe that’s fine. Maybe the center was always a fiction. But I notice I keep trying to narrate my Wrapped, to turn it back into a story—”This was my heartbreak year, this was my healing arc”—which suggests that even when I’m holding a bag, I want it to be a weapon. I want it to go somewhere. I want the mammoth to fall.

V.

Now look at what happens when the bag becomes a game.

Cozy games: an entire genre built on rejection of the hero mechanic. No combat. No conquest. No boss to defeat. Just gathering, tending, relating. You play as someone who collects shells. Who grows a garden. Who decorates a house that no one attacks.

This should be pure carrier bag. A way to play that doesn’t require anyone to lose.

Except.

In Stardew Valley, you’re trying to complete the Community Center. There are bundles. There are checklists. There are achievements for gathering every item, catching every fish, maxing every relationship. In Animal Crossing, you’re filling the museum—a collection that tracks toward completion, that rewards you for comprehensiveness, that tells you what you’re missing.

The games look like gathering, but they feel like conquest. The bag has been given a progress bar.

I don’t think this is a design flaw. I think it’s a diagnosis. We don’t want pure carrier bags. We want carrier bags that count. The form can change, but the hunger stays the same.

VI.

And then there’s “underconsumption core.”

The TikTok trend: people showing what they already own. Celebrating the modest closet, the single worn water bottle, the thing you didn’t replace because it still works. Anti-haul videos. The aesthetics of enough.

On its face, this is Le Guin’s vision made viral. Not acquisition but retention. Not conquest but care. The bag you’ve been carrying all along, finally held up to the light.

It was immediately criticized as “normal consumption core.”

Because for working-class families, for immigrants, for anyone who’s ever been poor—keeping things, using things until they’re used up, not buying what you don’t need—this isn’t a philosophy. It’s not an aesthetic. It’s Tuesday.

The people posting their “modest” collections were often not modest at all. They had chosen minimalism from within abundance. They were performing scarcity for engagement. Poverty cosplay.

The criticism was sharp and correct. But I want to push on something it revealed that I haven’t seen anyone articulate.

It’s not just that wealthy people were appropriating working-class habits. It’s that working-class people also build identity from what they keep. They also have relationships with objects. They also make meaning from the carrier bag. The difference isn’t economic—it’s theoretical.

My grandmother kept a butter dish that was older than my mother. She used it every day for sixty years. She never once called it “intentional living.” She never posted it. She never made it legible.

Carrier bag selfhood only becomes a theory when the people with platforms adopt it. Before that, it’s just life. It’s just what you do when you can’t afford to do otherwise.

And here’s the part that really curdles: The theory requires the essay. It requires me, right now, making the grandmother’s butter dish mean something. She just had a butter dish. I’m the one who needs it to be a philosophy.

The carrier bag, as a concept, might be what you develop when you’ve already won enough to describe your winning as something else.

VII.

Which brings me to the question I’ve been circling.

Is carrier bag identity what you adopt when you’ve given up on conquest? Or when you’ve already conquered and want a gentler story to tell about it?

The playlist is what you make when you can’t make the album. The second brain is what you build when you won’t write the book. The vault is what you fill when you can’t fill a stadium.

Or maybe it’s just a vault.

Is this liberation? Or just conquest in a linen shirt?

I notice that when I imagine letting go of the question entirely—just being a gatherer without wondering if gathering is defeat—something in me panics. Some part of me needs the pile to add up to something. Needs the bag to have a point.

Maybe that’s conditioning. Maybe I could unlearn it.

Or maybe Le Guin was right about what we do but the hero story is right about what we want. Maybe part of us will always want the arc. Will always want to matter in the way that heroes matter. Will always want the mammoth to fall, even when we know there is no mammoth, even when we know we’re holding seeds.

VIII.

There’s one more turn, and it’s the one I keep trying to avoid.

We’ve changed the form, but we kept the metrics.

The playlist gets measured by streams. The vault gets validated by what it produces. The TikTok gets judged by how many people it conquered. We’re building containers, but we’re judging them as weapons.

When I posted my Spotify Wrapped, I checked how many people viewed it. When I showed someone my Obsidian vault, I wanted them to be impressed by its size. When I kept things—saved things, gathered things, held things in my careful bags—some part of me was still hunting.

The container is constantly being asked to perform as a spear.

The container is constantly being asked to perform as a spear.

This might just be capitalism. It might just be the platform incentives, the attention economy, the way everything gets sucked into the scoreboard. Change the system and you change the game.

But I don’t think that’s the whole story. The scoreboard was there before the platforms. The scoreboard was there in my chest when I was ten, wanting to be the best at something, anything, wanting to win in a way that someone would see. The platforms amplified a hunger they didn’t create.

What would it look like to actually change the scoreboard?

I don’t know. I’m not sure it’s possible. The desire to matter, to be seen, to have the pile mean something—I don’t know how to separate that from the desire to be alive.

Le Guin believed you could tell different stories. She believed the carrier bag was a form that could hold different values, produce different worlds. She believed it so much that she wrote the essay, that she argued for it, that she—

That she tried to win the argument.

Even Le Guin wanted the mammoth to fall. Even Le Guin wanted to defeat the hero narrative. She was conquering with containers. She was hunting for a world where we could finally stop hunting.

Maybe that’s the only way. Maybe the bag can’t replace the spear. Maybe the best we can do is use the spear to defend the bag. Keep fighting for the right to gather. Keep arguing, conquering, winning the argument that winning isn’t everything.

It’s a paradox, but I don’t think it’s a cheap one. I think it might be the actual shape of being human.

IX.

Ursula K. Le Guin died in 2018.

Before she died, she said: “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.”

She believed in the container. She believed that there were other stories, and that telling them mattered.

I want to believe that too.

But I also want to stop pretending I’m only a gatherer. The pile isn’t content. The pile is still hungry. I’m still checking if anyone is watching.

Maybe the point isn’t to resolve the contradiction. Maybe the point is just to notice the bag in your hand and the spear in your other hand and to stop pretending you’re not holding both.

The playlist is a sack. But I made it because I wanted you to see it.

X.

Here’s what I kept today:

A nine-second voice note that says nothing important. A screenshot of a poem I’ll probably never read again. Three songs that only make sense in sequence. A photo of handwriting on a napkin—not mine, someone I’ll never meet, taken from a tea shop in a neighborhood I was passing through. The napkin said, in blue ink: “You don’t have to be whole to be good.”

I also kept a tab open for eleven days. It’s a flight to Copenhagen. I don’t know anyone in Copenhagen. I’m not going to Copenhagen. But I haven’t closed it, and I won’t close it, because something in me wants to believe I’m the kind of person who might just go. The tab is a lie I’m telling myself. I keep it anyway.

And: a four-second video of a toddler laughing at a banh mi. She looks maybe two. The banh mi isn’t doing anything. She’s just laughing. I don’t remember taking the video. I don’t remember the banh mi. But there it is, in the bag, and I can’t delete it, and I don’t know why, and I’m not going to figure it out, and that’s the whole point.

I don’t know why I keep any of it. It wasn’t for an essay. It wasn’t to prove anything. It was just a hand reaching out and something in me reaching back. A seed going into the bag because the bag was open, because my hands were free, because I was the one carrying it.

That might be surrender. That might also be the only true thing.

The bag holds both.

I’m still filling it. I’m still checking if you’re watching.

You are.